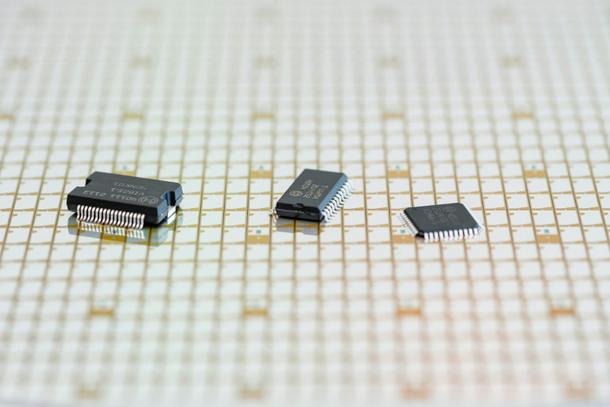

Carmakers epitomised the economic difficulties of 2021 as shortages of computer chips hampered their efforts to recover from a dismal 2020

Paris (AFP) - The world economy woke up from its pandemic-induced coma in 2021, but between the Omicron variant causing renewed disruptions and persistent inflation pushing central banks to pump the brakes, the outlook is uncertain.

Here is a look at the state of the global economy:

- Uneven recovery -

Countries have posted impressive growth figures as they clawed their way out of the depths of the 2020 Covid-induced recession, but some are faring better than others as wealthier countries have had better access to vaccines.

The United States has overcome its worst downturn since the Great Depression while the eurozone’s economy could return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year.

Many US employers had difficulty hiring enough employees to meet recovering business demand

But the rapid spread of the Omicron variant has prompted many countries to reimpose restrictions that are likely to hurt the travel and leisure sectors first and foremost.

With a single-digit vaccination rate, the economy of sub-Saharan Africa will grow at a slower click, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Most emerging and developing countries should remain far behind their pre-pandemic forecasts by 2024, the IMF says.

Central banks in Brazil, Russia and South Korea have raised interest rates to combat rising inflation, a move that could rein in growth.

China, the world’s second-biggest economy and a driver of global growth, is facing a slew of risks: New coronavirus cases, an energy crunch and fears over the debt crisis at real estate giant Evergrande.

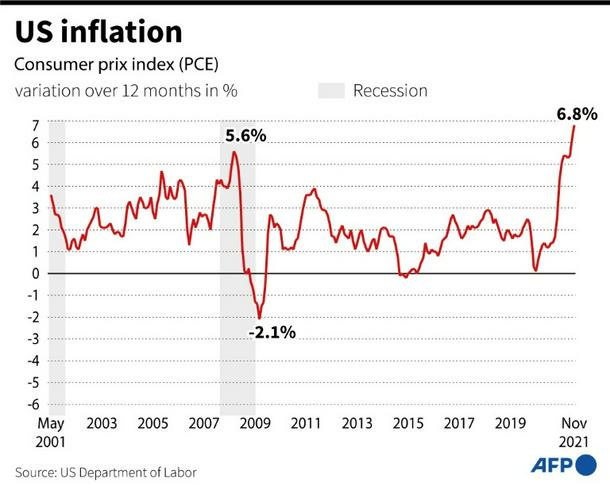

- Inflation soars -

Inflation has accelerated to multi-year highs around the world, as consumers returned with a vengeance and industries faced shortages.

Prices have soared across the board, with oil, natural gas and raw materials such as wood, copper and steel going through the roof.

“The biggest surprise of 2021 has been the goods-led inflation surge,” Goldman Sachs analysts wrote in a 2022 outlook.

Graphic showing the 12 month variation in percent of the US consumer prix index from 2001 to November 2021.

Central banks insisted for months that the inflationary pressure is a temporary consequence of economic activity returning to normal this year after it came to a halt when the pandemic erupted in 2020.

That changed in December, and the US Fed is now moving to quickly halt its pandemic support measures and expects to raise interest rates twice in 2022.

Stock markets have hit new record highs this year, and were overall reassured central banks are shifting to focus on keeping a lid on inflation.

“The question is whether we really are at the end of the crisis,” said Roel Beetsma professor of macroeconomics at the University of Amsterdam.

The IMF still forecasts 4.9 percent growth next year.

- Widespread shortages -

Industries have struggled to keep up with a surge in demand from consumers.

Global trade has been disrupted by insufficient shipping containers, congestion at ports and labour shortages.

Shortages of computer chips held back production of cars and some consumer goods

One key component that is hard to come by these days is semiconductors, chips used in everything from phones to video game consoles to the electronic systems of cars.

The shortage has been so bad that several automakers have had to temporarily halt production at some factories.

Labour shortages have added to the problem as truck drivers, port workers and cashiers have not returned to work following lockdowns.

Despite the difficulties, the IMF expects the world economy to grow by a healthy 4.9 percent next year.

- Climate change -

In addition to the pandemic, economies had to come to grips with another life-threatening event this year: climate change.

The conflict between economic growth and saving the planet came to the fore at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, this month.

Fires during heatwaves that experts have linked to climate change have caused much damage in parts of Europe and the United States

Nearly 200 nations signed a deal to try to halt runaway global warming after two weeks of painful negotiations, but fell short of what scientists say is needed to contain dangerous rises.

Droughts and other climate catastrophes threaten to further drive up food prices, which stood at a 10-year high in November, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Wheat has soared by 40 percent in the past year while dairy products are up 15 percent and vegetable oils reach new records.

“It’s pretty obvious. Everything has gone up,” said Nabiha Abid, a resident of Tunisia’s capital, noting that the price of meat has doubled.